- Home

- Alyssa Zaczek

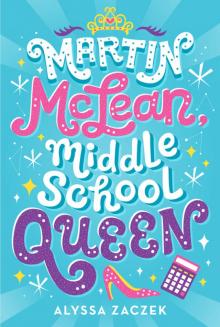

Martin McLean, Middle School Queen

Martin McLean, Middle School Queen Read online

BY ALYSSA ZACZEK

STERLING CHILDREN’S BOOKS and the distinctive Sterling Children’s Books logo are registered trademarks of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Text © 2020 Alyssa Zaczek

Cover illustration © 2020 Risa Rodil

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4549-3571-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zaczek, Alyssa, author.

Title: Martin McLean, middle school queen / by Alyssa Zaczek.

Description: New York : Sterling, [2020] | Summary: Seventh-grader Martin McLean has trouble expressing himself except at Mathletes competitions and now, as a female impersonator but his first-ever drag show falls on the same night as an important Mathletes tournament.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019018074 | ISBN 9781454935704 (book / hc_plc with jacket)

Subjects: | CYAC: Female impersonators—Fiction. | Mathematics—Competitions—Fiction. | Best friends—Fiction. | Friendship—Fiction. | Junior high schools—Fiction. | Schools—Fiction. | Single-parent families—Fiction. | Hispanic Americans—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.Z26 Mar 2020 | DDC [Fic]—dc23 2019018074

For information about custom editions, special sales, and premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales at 800-805-5489 or [email protected].

sterlingpublishing.com

Cover and interior design by Irene Vandervoort

For little Alyssa,

who never gave up on big Alyssa

Contents

September

1

2

3

4

5

October

6

7

8

November & December

9

10

January

11

12

13

14

Acknowledgments

SEPTEMBER

1

I hadn’t seen either of my best friends all summer, and I was so bored, time felt like it was moving backward. Carmen had been off with her mom on an architectural tour of Italy, and Pickle spent every summer with his elderly aunt on her farm. Frankly, I thought the summer apart took a much harder toll on me than it did on them. Sure, we kept in contact, but while they were off paddling gondolas and raising barns, I was forced to watch Property Brothers reruns with Mom for three months (“Ay, mira que rico they both are!”).

When she wasn’t swooning over reality TV stars, Mom spent the summer telling me I needed to work on “expressing myself.” That was easy for her to say. Mom’s an artist, and she was always creating. Her latest thing? A tropical-themed mural on our living room wall—a gigantic portrait of her whole family—which, of course, included me. I couldn’t help but wonder if the whole “expression” kick was her way of trying to force me to fit into her world. Mom’s world, the one of paint and color and ’80s dance music, is for people who like being center stage. My world is for people who would rather be in the audience. It’s a small world, my world, but I like it that way. I’ve found that being quiet is much safer than being loud.

Maybe that’s why Pickle, Carmen, and I work so well together. We’ve been a package deal ever since we met in third grade. Mom calls them parlanchines—chatterboxes—and when I can’t find the right words, they always have something to say.

Obviously, then, the first day of seventh grade was especially exciting, because I finally had my best friends back.

After lunch, we grabbed some prime real estate near the stairwell in the seventh-grade hallway to wait out the passing period.

“I haaaaate this,” Carmen moaned, slumping against the lockers. “Being on a different floor than last year sucks. My locker is on the other side of the building! I’ll never make it to the vending machines and get to drama rehearsal on time.”

“Consider yourself lucky,” Pickle said. “I can’t even reach my top shelves.”

“You couldn’t do that before.”

“Well, you don’t have to rub it in.”

Carmen Miranda was named after the singer with fruit on her head, even though her parents are Mexican, not Brazilian. She’s the giggliest person I’ve ever met, and she’s big in every sense of the word, right down to her personality. She has a gap between her two front teeth, and it makes her smile especially wide and pretty. I think some people get tired of Carmen because she never takes anything seriously, but I like that she has a sense of humor.

And Pickle is . . . well, he’s Pickle. His real name is Peter, but everyone has always called him Pickle, and no one really knows why. It could be because Pickle is generally pretty sour—Mom says he’s “self-deprecating,” always making fun of himself. He and Carmen get along because he cracks jokes about himself and she laughs, and that just makes him tell more. Pickle says he has a lot to joke about because he’s at least a whole foot shorter than most everybody in our class, and his ears stick out so far that sometimes he compares them to the handlebars of a bicycle. But I think Pickle really makes fun of himself so other people don’t do it first.

“You think Rafferty’s gonna make us play floor hockey again this year?” Carmen asked, changing the subject. She shuffled her brightly colored notebooks against her chest. “That was so miserable.”

“Better than the pickleball unit. The jokes that Charlie Chaudhari made. . .” Pickle shuddered.

“I heard they’re going to incorporate a dance unit,” I said. Actually, dance didn’t sound so bad to me. As much as I hated the thought of our whole class staring at me while I stumbled through a box step with some poor unsuspecting girl, at least there’d be no running involved. I don’t run unless someone is chasing me.

Just then, a pretty, dark-haired girl passed us in the hall and waved to us from her motorized wheelchair. Pickle turned the color of a cherry paleta. “H-hi, Violet,” Pickle stammered, raising a hand. Violet beamed and turned her chair toward us, meeting us by the lockers. I heard Pickle gulp from three feet away. Carmen giggled, delighted by his discomfort. Violet Levi is the girl that Pickle is massively, hopelessly in love with. She’s the first chair clarinetist in the school band, which is how Pickle got to know her. (He plays percussion; you should see him try to look at his music stand with a bass drum strapped to his chest.) It’s true that Violet is pretty—she has warm eyes and her hair, sleek and black, is the longest of anyone in our grade—but I think Pickle likes her because she’s basically the nicest person in Bloomington. She has never, ever made fun of his height, not even once.

Her adoptive parents, the Levis, named her Violet when they brought her home from Vietnam, and she loves her name. Like, really loves it. She color-coordinates everything she owns to it, including her wheelchair: various shades of purple, plum, lavender, and, of course, violet. Privately, Carmen and I find this to be a little eccentric. Pickle finds it adorable.

“Hey, you three!” Violet beamed. “Did you have a good summer?”

“It was okay,” I shrugged. “I read a lot of comics.”

“I saw the most amazing theater in Italy,” Carmen said with a wistful sigh. “Did you know they, like, invented masked theater? I mean, the Greeks started it and all, but the Italians basically made it go viral. Even if it was, like, the 1500s.”

“Cool!” Violet said, nodding appreciatively. “I went to sleepaway band camp in Indianapolis. We played a bunch of music by

Italian composers. I bet you would have liked it!” She turned her gaze on Pickle, who looked as though he was about to melt into the ground. “Did you do anything fun?”

“I, uh, um—I—well, so, um—I—farm? Farm. Farm,” Pickle spluttered. Carmen stifled a screech of laughter, perilously close to hysterics. Violet wrinkled her nose in confusion. “Farm?” Pickle repeated, looking at me with panic in his eyes.

“You . . . were on a farm?” Violet asked, glancing at Carmen and me for clarification. I blanched; poor Pickle.

“Yes!” I jumped in. “Yes. He was on a farm with his aunt. He actually helped build a barn. With his bare hands! Right, Pickle?”

Pickle nodded vigorously, and I swore I saw a bead of sweat form on his forehead. Violet’s smile returned, her braces laced tight with purple rubber bands. “Wow!” she said. “That’s amazing. I wish I could have seen it!” The one minute–warning bell buzzed overhead, startling Pickle so badly he jumped. “Oops, gotta head to English. We’ll have to catch up more later. See you in band!” Violet said, looking directly at Pickle. He whimpered.

“Ooh,” Carmen cooed at Pickle as Violet motored off. “I bet she would love to see you in gym, sambaing away!”

“Shut up,” he hissed. “I’m not dancing with anybody.”

“Violet wouldn’t be in gym class anyway,” I said. “She’s got an exemption.” Violet was born a paraplegic, which means she can’t use her legs and feet to walk.

“See?” Pickle said triumphantly. “Your dastardly plans are foiled, thou wicked woman.” He wriggled his fingers toward Carmen, who rolled her eyes.

“I never said you had to dance with Violet. Don’t be such a drama queen,” she said. Pickle gasped and pretended to clutch his chest in deep offense. “Come on, we’re going to be late for math.”

I had been looking forward to Mr. Peterson’s class, for three reasons.

1. Math is my best subject.

2. Mr. Peterson coaches Junior Mathletes and therefore likes me.

3. It’s the only class that Carmen, Pickle, and I have together, besides lunch.

All three of us sat in the front of the room by virtue of assigned seating. The downside to math class is that Nelson Turlington sat with us too.

“Well, if it isn’t Gordita Supreme and her two amigos,” Nelson sneered as we filtered into class. Carmen’s face grew blotchy with anger.

“Bite me, Turlington,” she said, her fists clenched.

“Sorry, my mom has me on a low-fat diet.”

“I’m surprised she has the energy to plan your meals. She must be exhausted from picking out all your outfits too,” Pickle shot back. Nelson’s upper lip curled. The problem with Nelson is that his parents are very rich and he is very handsome. I think this is something that probably plagues a lot of bullies. When you’re tall and tan and blonde, and your teeth are straight and your clothes are new and your hair isn’t coily, you can get away with a lot. Nelson seemed to be very aware of that.

“Awfully protective of the Chiquita Banana today, Pickle,” he observed. Nelson leaned back precariously in his chair. “I wonder if Violet has some competition?”

“Mind your business, Nelson,” I mumbled, settling into my desk. A strange, smug smile stretched across his mouth. He raised an eyebrow at me.

“Huh,” he said, “maybe she really does have some competition.” Before I could open my mouth to respond, the bell rang, and Mr. Peterson began walking toward the Smartboard at the front of the class.

“What does he mean?” Carmen whispered.

“Forget it,” I said, shaking my head. “It’s just Nelson being Nelson.”

Carmen stifled a tiny snort, but Nelson’s words echoed in my head. Maybe she really does have some competition. What did that mean? Did Nelson think I had a crush? On Pickle? Mr. Peterson passed around a syllabus and gestured to the board. Nelson doesn’t know what he’s talking about. Pickle likes Violet. Pickle likes girls. I like girls.

I think.

I hesitate to admit this, but in the interest of “expression” I think I should be honest. I’ve never actually had a crush on a girl before. Not ever. I mean, I like girls the way I like Carmen, but I’ve never like-liked a girl.

Does that make me weird? Everyone else seems to have had hundreds of crushes by now, but how can I really know what’s normal? Is there such a thing? It’s not as though the guys in my grade get together and discuss girls. Pickle’s the exception, but that’s different, because he only talks to Carmen and me and he only talks about one girl in particular. And Mom has definitely never talked to me about crushes or when it’s okay to like girls or any of that. I know some stuff thanks to the internet, but beyond that, nobody’s ever told me if not like-liking girls by now is normal.

And if I don’t like-like girls, does that automatically mean I like boys? Are those the only options? That makes me really anxious. Meadow Crest Junior High is a lot of things, but particularly accepting it is not. Back in fourth grade, when we were at Bloomington Elementary, Pickle and Carmen and I heard a story about a kid who came out as gay in eighth grade. They said he ended up having to switch schools because nobody would sit with him at lunch and people kept stealing his uniform during gym. I heard that someone beat him up at recess, too, but I don’t know if that’s true or not. It might all be an urban legend, but still: is that the fate that awaits me if I never have a crush on a girl? And how am I supposed to figure out who I am, when everyone else around me seems to know without having to ask themselves the question?

“Martin?” Mr. Peterson’s voice bore down on me, snapping me back to reality. “Are you still with us?”

“Huh?”

I looked up at him in surprise. Mr. Peterson is pretty young for a teacher, and he looks like an owl that was put through Willy Wonka’s taffy puller: all lanky limbs and long nose with horn-rimmed glasses and big eyes. He wears his lucky tweed jacket on the first day of school every year and also at the final Junior Mathletes competition every season. I found myself staring at his elbow patches as I struggled to remember the last thing he said.

“I asked if anyone in the class could define the Pythagorean theorem,” he said, pushing his glasses up to the bridge of his nose. He gestured widely to the class. No one had raised their hand. “I thought you might be able to help us out.”

“Me? N-no,” I replied, still shaking myself out of my thoughts. Mr. Peterson stared hard at me.

“No? That’s odd,” he said, “seeing how you helped the Mathletes take second place at Regionals last year using it.” He crossed his arms over his chest, waiting. Across from me, Pickle winced and put his head down on his desk.

“Dude,” he groaned. “Embarrassing.”

“Uh. Oh!” I stammered at Mr. Peterson. “The Pythagorean theorem. That Pythagorean theorem. Right. Um. It’s a²+b²=c². The square of the hypotenuse of a right triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the two other sides.”

“Very good,” Mr. Peterson said. He gave me a small smile before returning to the board. “I’m glad to see your lapse in memory was temporary. Chalk it up to the first day of school, yes?”

Still dazed, I didn’t answer. Carmen was giggling into her hand while Pickle tried to shush her. As Mr. Peterson continued the lesson, Nelson leaned over and whispered in my ear.

“Romantic daydreams, McLean?” Nelson snickered under his breath. “McLean the Queen. That has a ring to it, doesn’t it?”

My stomach dropped, then turned sour. My heart picked up in my chest, beating like it was trying to stage a prison break—tha-RUMP tha-RUMP tha-RUMP. I watched Carmen doodle stars in her notebook until my eyes glazed over, willing that distraction to drown out the thrumming in my ears. What is happening? Everything around me sounded as though I were underwater. Time had stopped moving. I realized I had doubled over like I had been punched in the gut. My throat was tight, and the air wasn’t getting to my lungs fast enough. I leapt up out of my chair, knocking it over with a metallic CLANG—

> And then it was just the pounding in my ears—

And the lights that were too bright—

And the silence that was too loud—

And—

tha-RUMP tha-RUMP tha-RUMP.

Every face in the room stared at me, blank and surprised—

tha-RUMP tha-RUMP tha-RUMP.

And I ran.

I just ran. My legs made the choice themselves, backing out of the room and scrambling out the door in one flash of movement. When my brain finally caught up with my body, I was halfway down the hall, gasping for breath. I put my hands on my knees and let my head hang. Great. Awesome start to the school year. Now everybody thinks I had botched brain surgery over summer vacation.

I sank to the floor, leaning my back against a bay of lockers. I closed my eyes, listening to my heartbeat slow. What was that?

“Martin?” I heard Mr. Peterson’s voice from down the hall. The sinking weight of embarrassment settled heavily in the pit of my stomach. I buried my face beneath my arms, my elbows resting on my knees. Mr. Peterson’s footsteps grew closer. He knelt down and tentatively put a hand on my shoulder. “Is everything all right?”

Obviously not.

I nodded into my arms without looking up. There was a shuffling and jumbling of long limbs, and when I shifted my head to peek out, I found Mr. Peterson sitting next to me. He peered down at me from behind his thick glasses, his brows knit together in a worried frown.

“I’m okay,” I said to the floor. “I . . . don’t know why I did that.”

“I know you’re a perfectionist, Martin, but believe me, everyone zones out in class from time to time. Even straight-A students like you,” he replied.

The voice inside me wanted so badly to tell Mr. Peterson about what Nelson said to me, about how it made me feel sad and scared in a way I couldn’t put my finger on. I wanted to tell Mr. Peterson, but I didn’t. Instead I nodded solemnly.

“I know.”

“Okay,” Mr. Peterson said. He took off his glasses and polished them with the corner of his plaid shirt. “Martin,” he said, blinking as he placed the glasses back on his nose, “have you had panic attacks like this before?”

Martin McLean, Middle School Queen

Martin McLean, Middle School Queen